Michaela Goade

Michaela Goade

Painter and Children’s Book Illustrator

Michaela in her element — photo by Sydney Akagi

Interview by Hailey Hirst

Michaela Goade is a water color painter and illustrator based in Juneau, Alaska.

Her work varies widely—from landscape vignettes and personal projects to fully illustrated children’s books—but together it feels wholly cohesive in mood, color palette, and the spirit of wonder that runs as a constant theme.

Within the last couple years, Michaela has found her niche as an illustrator in Indigenous KidLit. Here she not only brings the vivid details and colors of the Alaskan coast to life, but also ancient Tlingit stories and other topics of cultural importance.

In getting to know more about Michaela and her artistry, we were interested to find out how the landscape of Alaska, her Tlingit heritage, and aspects of storytelling all meld together in her creative work.

Unsurprisingly, her answers are as delicately crafted as her paintings are detailed.

Find out more, in Michaela’s words:

Meet Michaela Goade

Which landscapes influence your work and color palette the most? What details do you love to capture?

I am deeply inspired by the coastal wilds of Southeast Alaska, traditional territory of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian nations.

We are nestled in the Tongass rainforest—a labyrinth of islands and waterways, mountain ranges and ice fields. Life is oriented around the relationship between land and sea, a theme I seem to be constantly drawn to.

- Photo by Sydney Akagi

“City by the Sea” by Michaela Goade

I work to capture the feel of this environment whether it’s through the seemingly endless shades of blues, greens and grays, the way mist and light interact with the trees and waves, or the beautiful animals and plant life that call this region home.

Overall my mind is usually lost in the magic and ethereal beauty of Southeast Alaska, and I’m always on the lookout for moments that move me and the stories they inspire.

I also like to think of creating art as an act of reciprocity, a way to express my gratitude for Mother Earth. It becomes a reaction, a conversation, one way in which I can help defend her. It’s motivating to think that maybe, through my work, I can help others do the same.

Culture is an important aspect both to your style and the subjects you depict in artwork. You even say that the artist path enabled you to reconnect with your culture. Can you tell us more about your background and the art/culture connection?

I am of mixed Indigenous and northern European heritage. I identify most with my Tlingit heritage, largely due to where I grew up surrounded by family and culture.

Although I was raised with a foot in each world, childhood was largely influenced by white culture. This in turn resulted in identity issues that I’m still working through today. Growing up, I often felt ashamed of my Tlingit heritage and distanced myself from it. There was a lot of racism in my town and I didn’t feel the pride that I should have.

Now, I often feel guilt and shame for not being Native enough. It’s a cruel cycle, and not one I’m proud to admit, but it’s very important to address.

As I’ve grown older, I can look back and see my childhood and adolescent shame as partly due to colonialism at work, a product of trauma passed down through the generations. Of course, my own insecurities were also at play. Working through these identity issues helps me better understand the bigger picture and informs my choices moving forward.

“Misty Forest” by Michaela Goade

I first began illustrating picture books a couple years ago with my tribe. They were creating books by Native people for Native people, and it was an opportunity I embraced. I’ve always been drawn to storytelling in its various forms. Likewise, I’ve always considered myself an artist in some way or another.

Picture books spoke my language like nothing before had. They became a way to reconnect with my culture, find my artistic voice and give back to the Native community in a unique way. I feel very grateful to be doing this work. I’m able to help create respectful and accurate representations of Indigenous peoples in children’s publishing.

Children’s books are reflections of our society. They often communicate who is visible and important in today’s world. Therefore, representation that reflects the very diverse experiences of Native Americans is much needed. It is deeply inspiring and engaging work, and I want to keep working to honor and lift up Native people from all nations.

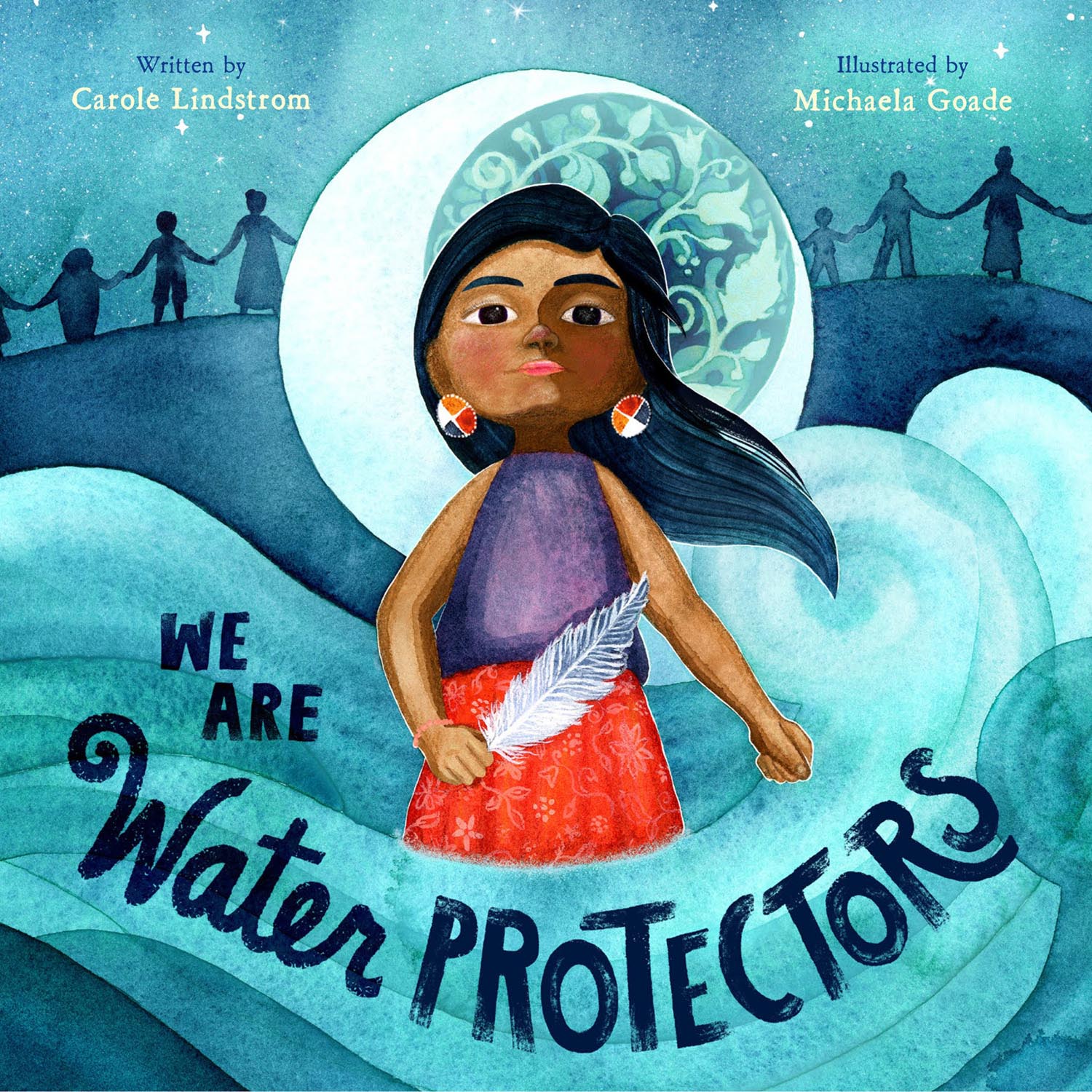

From the book “We Are Water Protectors”

You illustrate picture books, but a lot of your other work seems to incorporate aspects of storytelling as well — whether it’s an informative story of toxic plants or a clouded landscape that tells us a storm is either just passed or on its way. What do you like about telling stories visually?

What a lovely question! My brain tends to think in concepts, themes, and stories. It is difficult for me to finish something that I don’t have a deeper connection to. It quickly becomes obvious if I’ve set out simply to make something pretty. In the age of Instagram, this can be a challenge and I’ve learned the hard way. So I think what I love most about telling stories visually is the personal connection it can create between so many strangers. We all love stories!

One of my illustrations called “Crab Harvest,” shows a father and daughter out on the ocean pulling up their crab pots. It is amazing how many people have told me personal stories they attached to that one piece. Some folks remembered days on the water with their father or grandfather, others saw their own children, nieces, cousins, friends, etc.

“Crab Harvest” by Michaela Goade

“Toxic Plants” by Michaela Goade

Visual storytelling can stir up powerful nostalgia for family and place, a theme I believe to be integral to who we are as humans. I love being able to create and share pieces that move people. And I’ve found that it can be especially powerful when it speaks to the wonder of childhood, a time when everything was magical, sometimes unknown and scary, but often a time worth remembering.

What are you working on right now that excites you?

I’m about to begin the painting process for the next picture book I’m illustrating, which is always an exciting albeit intense time. I’ve also been working on crafting the story for my author-illustrator debut, which has been a very rewarding experience so far. I also sell quite a bit of art around the holidays, so I’ve begun a number of personal pieces and projects that have been in the back of my mind for awhile.

- Book development

- “Encounter” book process

I also just had a book birthday! The first picture book I illustrated for a major trade publisher came out earlier this month. It’s called “Encounter” and was written by Brittany Luby and published by Little, Brown for Young Readers. It’s been a wonderful journey so far.

Another book I illustrated, “We Are Water Protectors,” written by Carole Lindstrom and published by Roaring Brook Press, comes out in March and I’m so excited for that one!

Learn more about Michaela Goade on her website, michaelagoade.com, and see more of her artwork and creative projects on Instagram @michaelagoade.

Be the first to comment