On Wilderness

On Wilderness

By Emma Longcope

Increasingly, land is parceled off and designated as “Wilderness.” What does this perhaps-overused term mean to the modern adventurer? A bridge over the gap between recreation and conservation is in order.

I.

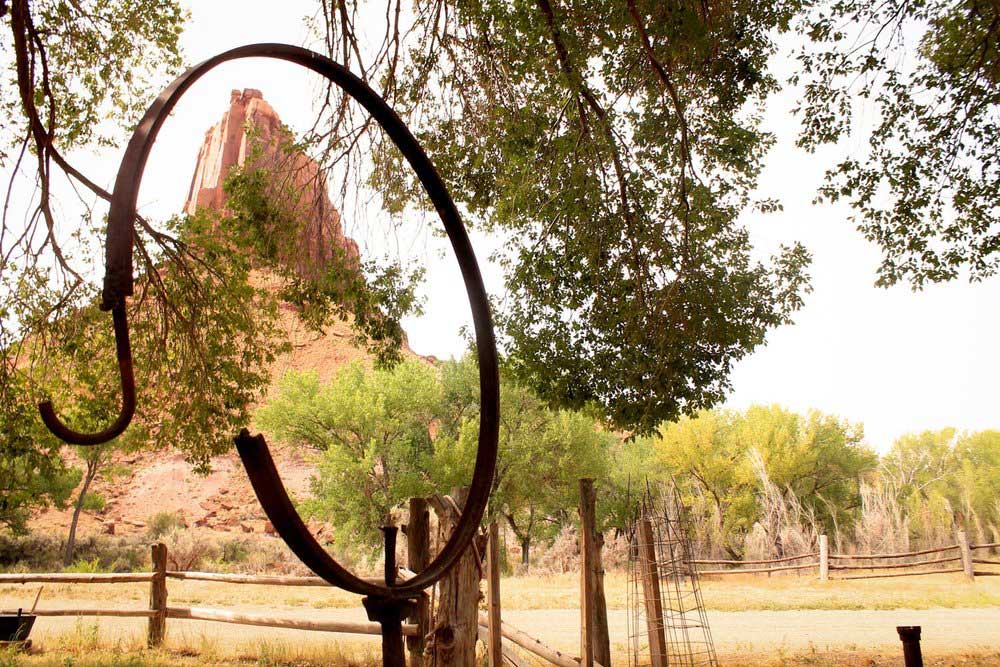

Let’s take our imaginary Sprinter vans to the trad climbing hotspot Indian Creek, Utah. Let’s go to Dugout Ranch, nestled at the base of those sandstone cliffs. The sagebrush between the dry grass and rust-red rock shimmers in the stifling desert heat. Cattle move slowly, chewing lazily, ambivalent toward our complaints about the climate. The shade of the cottonwoods provides little relief. We walk through the dusty land in a daze until we come to the home of ranch owner Heidi Redd. [In this instance, I visited the Creek as a researcher for the State of the Rockies Project and had the opportunity to interview Heidi on the topic of large-scale landscape conservation.]

“It used to be that if we saw car lights driving down the road, we knew they were visiting us [at the Ranch],” Heidi tells us. “There was nowhere else to go.” She has written her stories onto this landscape and has witnessed the changes it has endured.

“It’s easy to remember a time, 50 years ago, when you never saw a soul, and it was easy to think of it as all yours.You were the only one. Then, boom, the Park.”

“It is easy to remember a time, 50 years ago, when you never saw a soul, and it was easy to think of it as all yours. You were the only one. Then, boom, the Park.” Heidi refers to Canyonlands, established in 1964, the same year Congress passed the Wilderness Act.

In 1970, a paved road to the Park cut through Dugout Ranch’s property – the same paved road we climbers drive to access those beautiful sandstone splitter cracks. “If you live on the land,” she says, “you see slow changes happening. You know what’s going on.” As Heidi speaks, I pick out the hum of car tires on asphalt underneath the cattle’s insistent groans. “Wilderness,” Heidi says with a small laugh. “I guess that’s what everything used to be. Now, I guess it’s just over there-” she points toward Canyonlands.

By defining Wilderness as removed from humans, legislation fences out anyone who wishes to live off the land. Is this fencing a necessary move to save landscapes from today’s bustling world? Are there alternatives?

II.

Let me backpedal. I’m bringing this up because I believe that – as travelers, as explorers, as recreationists – we need to be just as passionate, if not more so, about being conscientious global citizens.

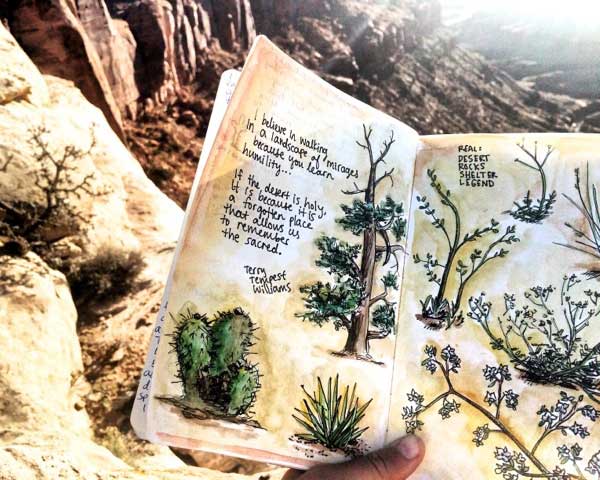

“Wilderness is not a luxury, but a necessity of the human spirit,” Edward Abbey famously declares in Desert Solitaire, “and is as vital to our lives as water and good bread.”

As a conservationist, artist, and recreationist, as a wanderer and wonderer, I am fully in agreement with the sentiment that our human souls require wild places. Yet much has changed since Abbey lived in the desert.

According to the Wilderness Act, “in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, [Wilderness] is an area… where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Wilderness is untrammeled, uninhabited, and inhospitable: defined by what it is not. It is the absence of humans; it is our removal from our natural environment. The Act has designated 758 official Wilderness Areas and preserved nearly 110 million acres. Without it, this land would have potentially been available for extractive or harmful industries, so it is “saved”.

There is a tension, now, an unwillingness to let go of the idea that what is wild is pure, and we are separate from that.

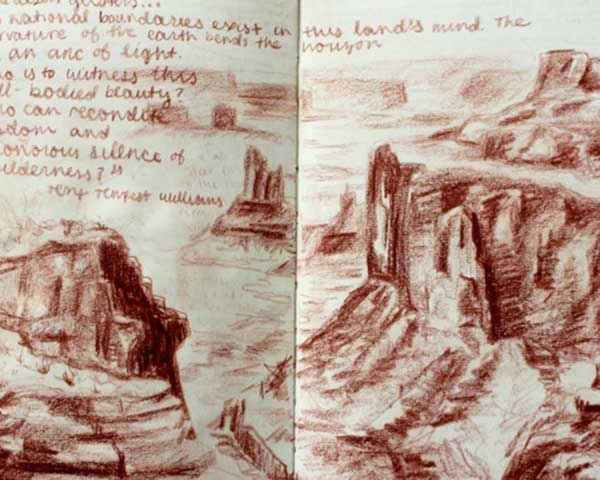

In his essay Desegregating Wilderness, Jourdan Imani Keith explains some potentially troubling elements of the designations. “Segregating wilderness from people creates permission to deforest and devalue the landscape where people are allowed to ‘remain’,” he writes, “while falsely defining the remote landscape as ‘pristine’.” We tend to love where we live and protect what we love. If we are separated from the Wilderness by enough distance that we do not consider it home, or at least tied to our sense of place in this world, we are less likely to take a stand for it.

“The problem,” Roderick Nash wrote in a 1978 essay, “is that the traditional meaning of wilderness is an environment that man does not influence, a place he does not control.” We cannot parcel off masses of Earth for separate purposes: here we work, here we create, here we do not go. There is too much overlap, too many conflicting interests. It is too hard to form a connection to a regulated land.

There is a tension, now, and unwillingness to let go of the idea that what is wild is pure, and we are separate from that. We cannot integrate ourselves wholly into the wild, lest we risk turning the wild into another civilization, with paved roads in parks and vending machines at every turn. Yet we cannot remove ourselves fully because the human spirit thrives on the unknown, the to-be-experienced.

III.

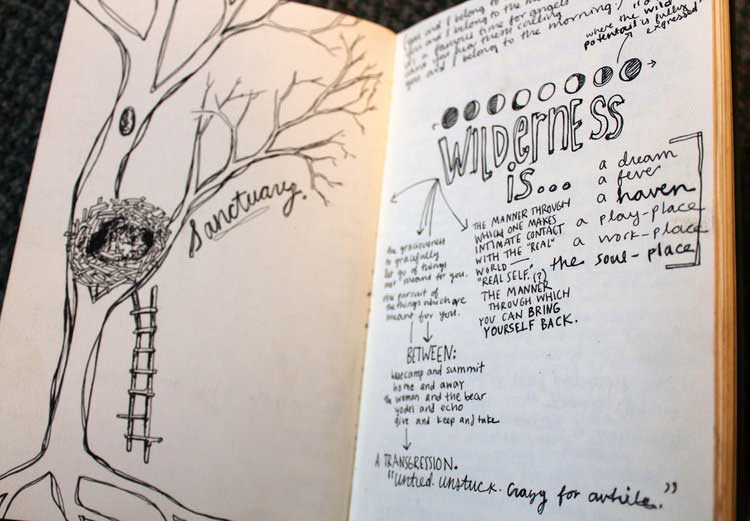

As we continue to investigate the extent of the boundaries between ourselves and our land and work to find the most natural relationship possible, it is crucial only that we continue to question. How do our definitions morph to reflect our society? How can conservation efforts take these various meanings into account?

We must find a way to merge wilderness and our own beings, for the preservation of all.

“Nature is not a place to visit. It is home,” wrote poet and activist, Gary Snyder. We must find a way to merge wilderness and our own beings, for the preservation of all. We as individuals, as natural as the pines and streams, must learn to function as catalysts for connection and for balance – whichever winding paths we choose to follow.

Find Emma Longcope on Instagram and read more of her writing on her website.

Be the first to comment