Solo on Mt. Shasta, an Ancient Hike

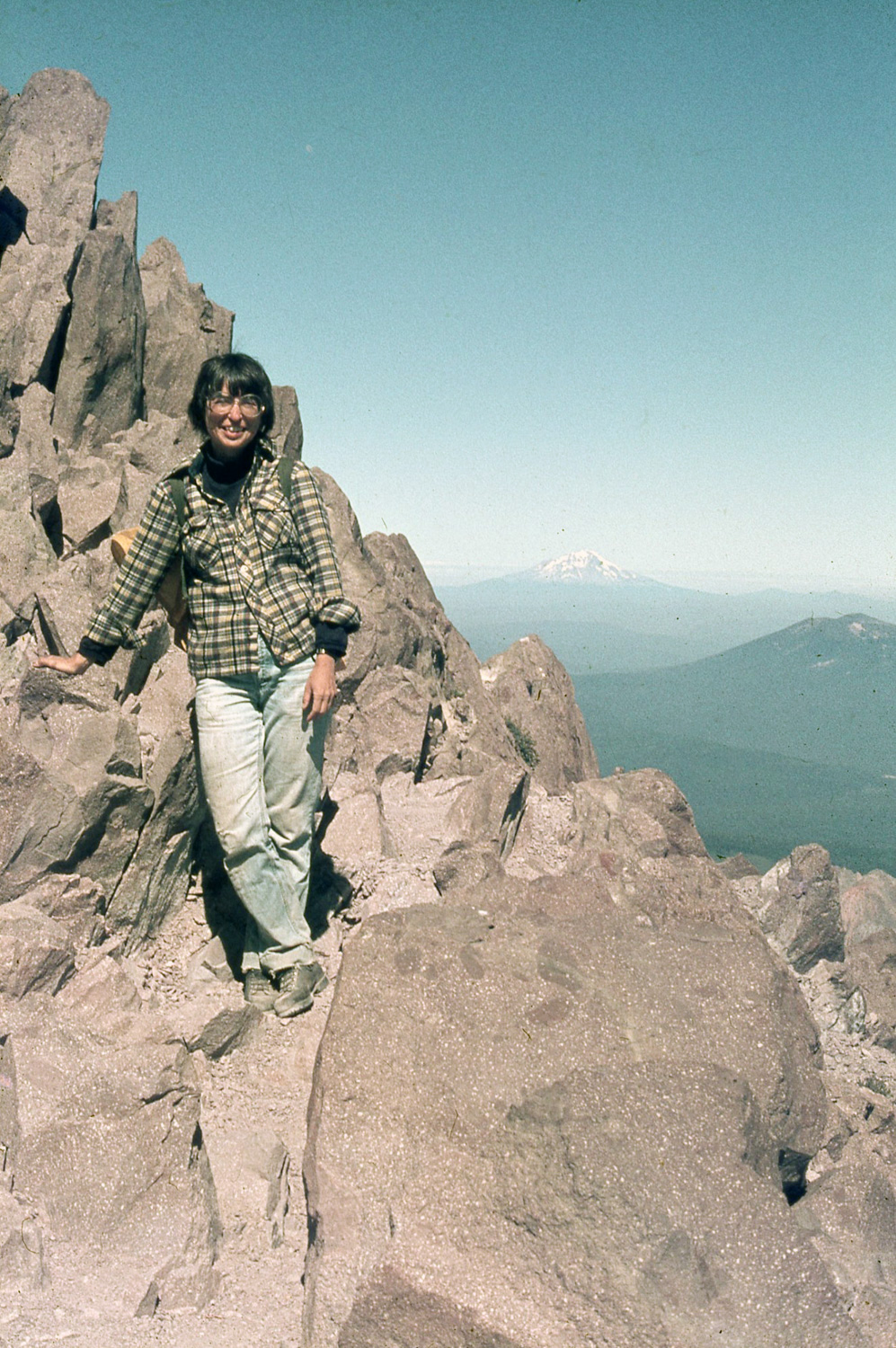

Words & photos by Joanne Blondin

Surrounded by snow, ice, ink-black rocks, and the smell of rotten eggs, I was finally sitting on top of a dormant volcano—Mt. Shasta, 14,180 feet above sea level, 265 miles northeast of San Francisco, September, 1982.

I felt privileged that the mountain permitted me to sit on her peak for an instant. I was almost completely alone. Except for Robert and me, nothing else was alive. Not a bird. No moss or lichens. Not a scrap of green. I made it. But could I find my way back?

I had hiked alone for most of the day. Take four steps; stop, catch my breath; take four steps; stop, catch my breath over and over again. Robert, the caretaker at Horse Camp Lodge, had suggested that I take slow steady steps, but my legs kept trying to hike at my usual swift, sea level, flatlander pace. My lungs would not cooperate. Every breath burned and then I could barely get a breath. The air was too thin. The altitude was twice as high as the 7,000 feet where I had been camping and acclimating. I was not hungry or thirsty. I had eaten breakfast at 7 a.m. and strangely, at noon I had to force myself to have a sandwich. Suddenly it was 5:30 p.m. and the sun would set at 7:30 p.m.

This was my second attempt. A week earlier I had tried to reach the top of Mt. Shasta from Ski Bowl Lodge on the south side of the mountain. Then, I naively thought that since ropes and pitons were not required, I could just walk up the mountain. The trail was unmarked, so I followed a ridge that appeared to go to the top. I had hiked above tree line before in the East and did not expect rain in California in September.

From the top of Lassen Peak, I saw Mt. Shasta in the distance. I felt an irresistible pull from the mountain. On the hike down from Lassen, all I could think about was: how can I climb Mt. Shasta? I had to try again.

That first time, I admired the courageous flowering plants growing where there appeared to be only rocks and no soil. I took lots of photos so I could focus on them instead of my fear of hiking alone in an unfamiliar area 3,000 miles from home.

During that first effort, my head began to ache in the early afternoon. As I continued, my headache grew worse and my hiking slowed. I had never had a headache while hiking before. (I later learned that it was a symptom of altitude sickness.) The snow-covered peak seemed no closer. I realized that I could not reach the top in daylight or even that night. Sensibly, I retraced my steps and left the mountain.

Yet, the mountain had not left me. For the next several days I camped and hiked 80 miles southwest of Mt. Shasta in Lassen Volcanic National Park at about 7,000 feet. There I took a wide, relatively easy trail to the top of another dormant volcano, Lassen Peak, 10,457 feet high.

From the top of Lassen Peak, I saw Mt. Shasta in the distance. I felt an irresistible pull from the mountain. On the hike down from Lassen, all I could think about was: how can I climb Mt. Shasta? I had to try again.

I read the directions in a small paper brochure from the Forest Service: “Mt. Shasta, A Climber’s Guide from the Shasta-Trinity National Forests.” I rented crampons and an ice axe as suggested, although I was not sure how to use either.

The Guide also said, Do not climb the mountain alone. I ignored that caveat. I would be solo hiking Mt. Shasta. I decided to start from Horse Camp, a lodge slightly closer to the top. I strapped my sleeping bag on my army surplus daypack, carried my tent in my arms, and hiked the two and a half miles to the camp.

At Horse Camp, I set up my tent and built a fire to boil water for my freeze-dried dinner. Up over the trees, over the lower slopes of the mountain, I watched clouds whizz into view and be torn apart by a ferocious wind. I could not hear the wind, only see its effects. That was where I would be hiking the next day.

Robert, the Horse Camp lodge caretaker, came over and chatted by my campfire. (The lodge was for emergencies only.) He provided a very different view of Mt. Shasta. “Mt. Shasta is one of the seven places in the world where spirits live.” He told me, “There are giants, who can be in physical or spirit form, living on the mountaintop. Legends describe them as seven feet tall and blue. They are from the lost continent of Lemuria that sank in the Pacific. Now the spirits/giants live in a city several miles beneath Mt. Shasta.”

Editor’s note: The prominent volcanic peak is a significant and spiritual place in Indigenous tribal myths and stories as well. It lies within the territories of the Shasta, Wintu, Achumawi, Atsugewi, Klamath, and Modoc tribes, and appears in creation stories and other lore.

Robert wanted to hike with me the next day. In spite of being uptight about hiking alone, I wanted to hike at my own pace. I told him that I would move too slowly. He told me he would start up the mountain later in the day.

The next morning was bright blue and cold. The clouds from the previous day had been blown away.

Jennifer, one of the women I had met at a campground before my hike to Horse Camp, told me she would talk to the mountain spirits for a sunny hiking day. Apparently, she had made contact. It was cold enough to wear my down jacket, long underwear, and ski cap. I carried five or six peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, water, and a flashlight. In my jeans back pocket for security and courage, I brought the keys to the rental car.

Before leaving, I reviewed the information in Mt. Shasta, A Climber’s Guide: From Horse Camp, (7,900 ft.), head uphill, follow Avalanche Gulch to Lake Helen at 10,400 ft. Lake Helen is a shallow glacial depression and usually dry.

The beginning of the trail was constructed from stones carefully set in place by a former caretaker. Soon the handmade trail ended, and I continued my hike by looking for the landmarks described in the Guide. There were no trail markers. Lake Helen was dry and rocky. Only its flat surface made it distinct from the mounds of rocky rubble I was hiking over. Above Lake Helen, stay to the right of an island of rock shaped like a heart.

The black rock contrasted with the snow. I had seen this island from below. Do not ascend the steep slope to the left of the heart. Loose rocks are constantly breaking free and falling on this side. I heard rocks falling to my left.

As you approach the distinctive ‘Red Banks’, go up a chimney to the top of the banks. The chimneys are usually icy and dangerous, and crampons must be worn.

When I reached the third chimney, I was able to scramble up it without crampons. From the top of the banks, walk up the gentle but arduous rock slopes and ridges to the summit plateau at 14,000 feet. I had resisted putting on crampons. Finally, when I could not pick my way around the ice and snow, without sliding, I used them. I hiked up and up. Except for the occasional stain of red-brown algae in the snow, nothing around me was alive. Finally, there was no more snow. On a pile of rocks, I took off my crampons and looked at my watch. It was 4:15 p.m. and the summit was still ahead.

I had been hiking for nine hours. I knew the sun would set at 7:30. Could I come down in the dark with no trail or sleep out on the barren mountain. How long would the return trip take? I was reluctantly considering turning around. Then I spotted Robert hiking up the mountain below me.

He caught up with me and said, “The top. It’s no problem from here.” We climbed on together.

The very last steps to the top were covered with ice. With one improperly placed crampon-less boot, I could slip and never tell this story. I was very aware of my fragility. Finally, with her permission, I sat on the top of Mt. Shasta.

It was still daylight. I looked back the way I had come. The green forest below was very, very far away. I had no time to explore the peak. I knew my instant on the mountain was over. As I started down, I wandered over a bare area. There I smelled the strong odor of rotten eggs. Mt. Shasta was still venting gasses.

When we got to the snow, Robert said, “Sit down and slide. Use your ice axe as a brake.”

I sped down rapidly, but not fast enough to avoid hiking down in the pitch black night. Robert, hiking much faster than I, said “I’ll go down first and put a candle in the window of the lodge. You can walk toward the candle to find your way. Take a left at the third snowdrift and head straight down.”

I repeated his words over and over like a mantra. I was not sure which snowdrifts he meant. With a flashlight in hand, I hiked down.

“Take a left at the third snowdrift and head straight down.”

Suddenly on a distant hill to my right I saw a man in a green parka lying by an orange tent. Impossible! That hill is just a pile of rocks and cinders. No one could be camping there. I must be hallucinating, I thought.

“Take a left at the third snowdrift and head straight down. Look for the candle in the window.”

The man in the green parka remained on the hill as I trudged past. Now on my left I saw a bright light on top of Green Butte. Green Butte is just a pile of volcanic ejecta. That light is too bright to be a candle. Another hallucination. Do not think about it. Focus on my next step. The light remained bright as I walked past.

I heard a dull thud ahead of me. The thud was real. The vibration felt like a boulder large enough to break a bone or knock me out.

“Robert?” I shouted.

Silence.

“Who’s there?” I yelled.

Silence.

I reassured myself that the thud was not a legendary blue giant, just a loosened boulder. Then I worried about the constantly falling rocks the Guide warned about. Had I strayed too far to the right in the dark?

“Take a left at the third snowdrift and head straight down.” Where is the candle in the window?

At last! Finally! There was the candle very faint, far ahead, and below. I stumbled toward it. When I got to the lodge, I could see a glow on the other side. I found Robert sitting by a roaring campfire with pots of hot food.

“I found the third snowdrift! Thank you for putting the candle in the window,” I exclaimed to Robert, “I couldn’t have found my way down without it!” I did not mention the apparition.

Soon I was eating hot vegetables and millet and drinking comfrey tea. Robert had made dinner for me. I ate as much as I could, in appreciation, even though the altitude still dampened my appetite. My adventure did not end here.

As I crawled into my sleeping bag after 15 hours on the trail, I felt for my car keys and discovered that the back pocket of my well-worn jeans had ripped off. My car keys were gone! I’ll think about that tomorrow, I thought, as I fell asleep.

I reassured myself that the thud was not a legendary blue giant, just a loosened boulder. Then I worried about the constantly falling rocks the Guide warned about. Had I strayed too far to the right in the dark?

The next morning, I hiked out knowing that my car keys were somewhere on the clouded-over mountain. When I got down to the parking lot, no one was around to ask for a lift, so I decided to hitchhike into the town of Mt. Shasta to find a locksmith. Many cars passed me, although I thought I looked non-threatening even with crampons and ice axe dangling from my army pack. Finally, a white-haired old man in a jeep stopped for me.

“You’re the first one to stop.”

“There’s a murderer at-large around here. Everyone’s talking about it,” he explained. (Many years later, I had no luck finding information on the internet about a murderer in 1982 in the town of Mount Shasta.)

After I phoned to get the car key-code numbers, he drove me to a locksmith. While the locksmith made a new set of keys, I stared with incomprehension at his television. I had been living in a tent for over a week. The locksmith and I took the new keys up to the car. The keys got me into my car but would not start it. We returned to the locksmith’s house and he made a second set of keys. This set worked!

I drove to the campground where I had met those two fellow women hikers, Jennifer and Kitty, several nights before. I thanked Jennifer for speaking with the mountain spirits; my hiking day had been perfect.

Then, I talked and talked about my adventure to my captive audience.

When I returned to my tent, I found this note:

‘Joann, We found the keys to your rented car today, when we came down from Shasta. The keys are under the front bumper on the passenger side. Sue & Jodi’

How could they have found them on a mountain with no trails and known they were mine? How could they have retraced my steps? Was the mountain looking out for me? I asked around at many other campsites, but no one knew Jodi and Sue.

The next morning Jennifer said I should have hitchhiked back to the campground and gone to a hot mineral spring with them for a relaxing day, instead of finding a locksmith. She said that I was a day out of sync with the universe. I did not feel that way.

I felt that Mount Shasta had been benevolent, that her spirit was now a part of me. That connection and my own self-reliance helped me persevere in the cold thin air, before cell phones and the internet were ubiquitous. I hiked up and back, putting one foot on the ground and then the next over and over again.

🙂 thank you for the read

So nice

Thank you for sharing, beautiful story