Woman on the Watch: Field Notes from a Fire Tower Lookout

Woman on the Watch:

Field Notes from a Fire Tower Lookout

By Trina Moyles

Days at the tower were long and taxing. The sun pounded down on the forest. Day after day, the cupola occupancy level was designated extreme. “Extreme” meant I would have to spend eleven hours in the cupola, from 9 a.m. till 8 p.m., with only a brief thirty-minute break to prepare a quick lunch, refill water bottles, and gather temperatures for the afternoon weather report.

I began to feel more robotic than human.

Every day was a replica of the previous one: Wake up at 6:30 a.m. Make coffee and oatmeal. Wash the dishes, sparingly, with a damp cloth. Make my morning climb to check for smoke, visibility, and cloud cover. Do my morning weather report. Pack lunch and water and snacks for the day. Try to call Akello: bad reception or, worse, no answer. Climb the tower for 9 a.m.

Watch for smoke.

12:30 p.m.: Climb down. Go pee. Refill water bottle. Eat lunch. Pat the dog. Take weather calculations. Rush back up the ladder to deliver my weather report at 1 p.m.

Watch for smoke.

Trina’s cabin with tower and cupola rising above

Inside the cupola with spotting scope and other lookout tools

Try to read a book, Rebecca Solnit’s A Field Guide to Getting Lost, but the words become ants swarming the page. By mid-afternoon the cupola is hot. Too hot. Bloody hot. Solar oven hot. Remember watching a demonstration in rural Nicaragua, a woman frying an egg under the glass lid of a solar oven. Consider the glass windows of your cupola.

Think to yourself, I am the egg.

Pee in a yogurt container. Feel ashamed. Fling your shame out the window.

Watch for smoke.

Want to sleep. Poke yourself in the ribs. Stay alert. Watch for smoke. At 7 p.m., stand by the radio. Listen for your call sign—567—and your occupancy level for the following day: extreme, high, moderate, low-moderate, low. But what was the point? I already knew my fate. Another day without rain meant another eleven-hour day in the cupola.

Watch the vanishing light make the forest shadowed and golden and beautiful.

Climb down to the dancing dog at the bottom of the tower. Feed dog. Feed self. Put on gardening gloves and hack at wild rose bushes in the garden beds. Pull weeds. Build a compost heap. Swat mosquitoes. Haul water in five-gallon pails from a nearby swamp.

Plant seeds.

Retreat to the cabin. Run a damp cloth over exhausted body. No rain, no shower.

Blow out the candle. Listen to the dog, already asleep, her chest rising and falling.

Close eyes. Push away the loneliness. Dream deep. Dream hard.

Wake up. Do it again.

—

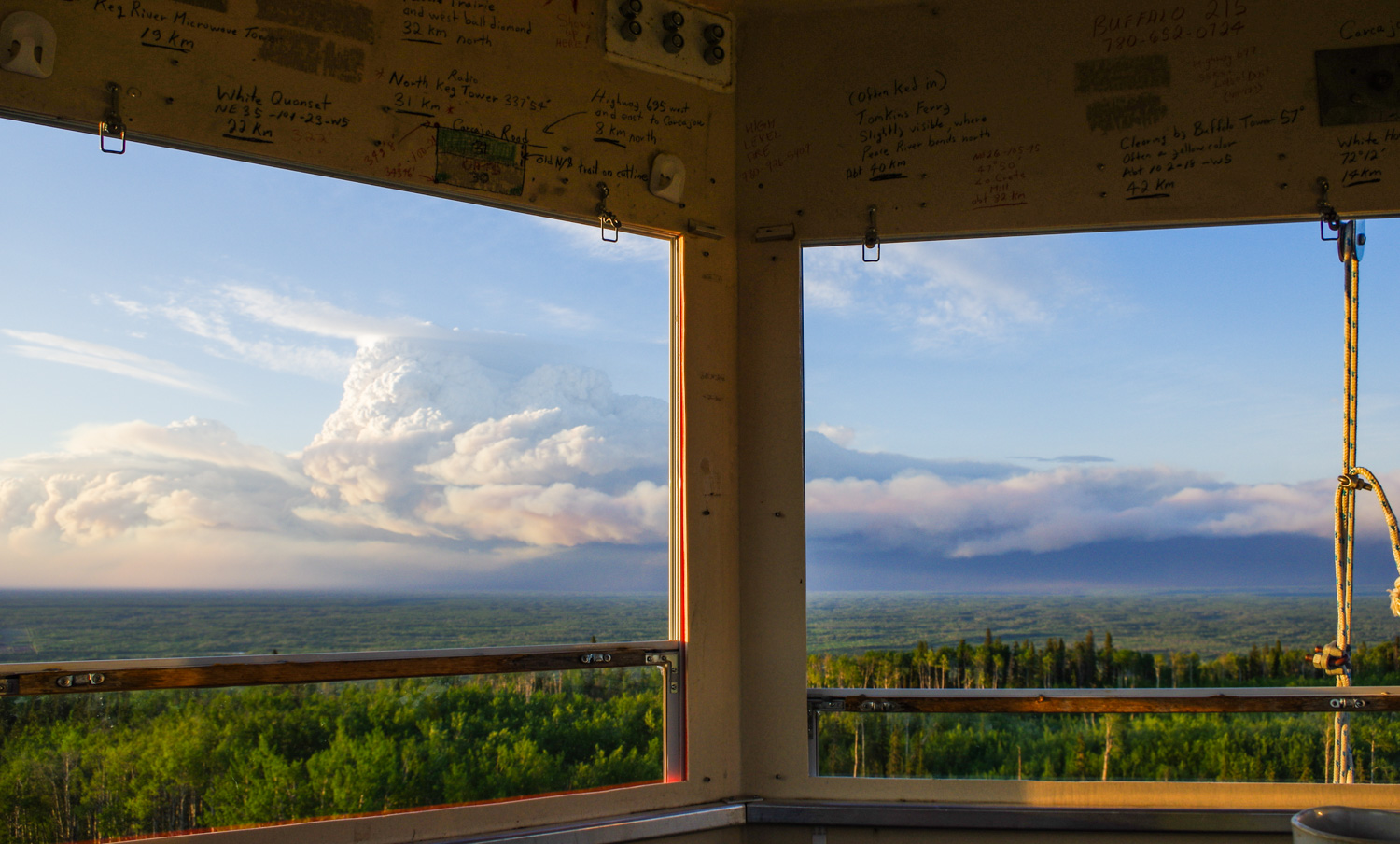

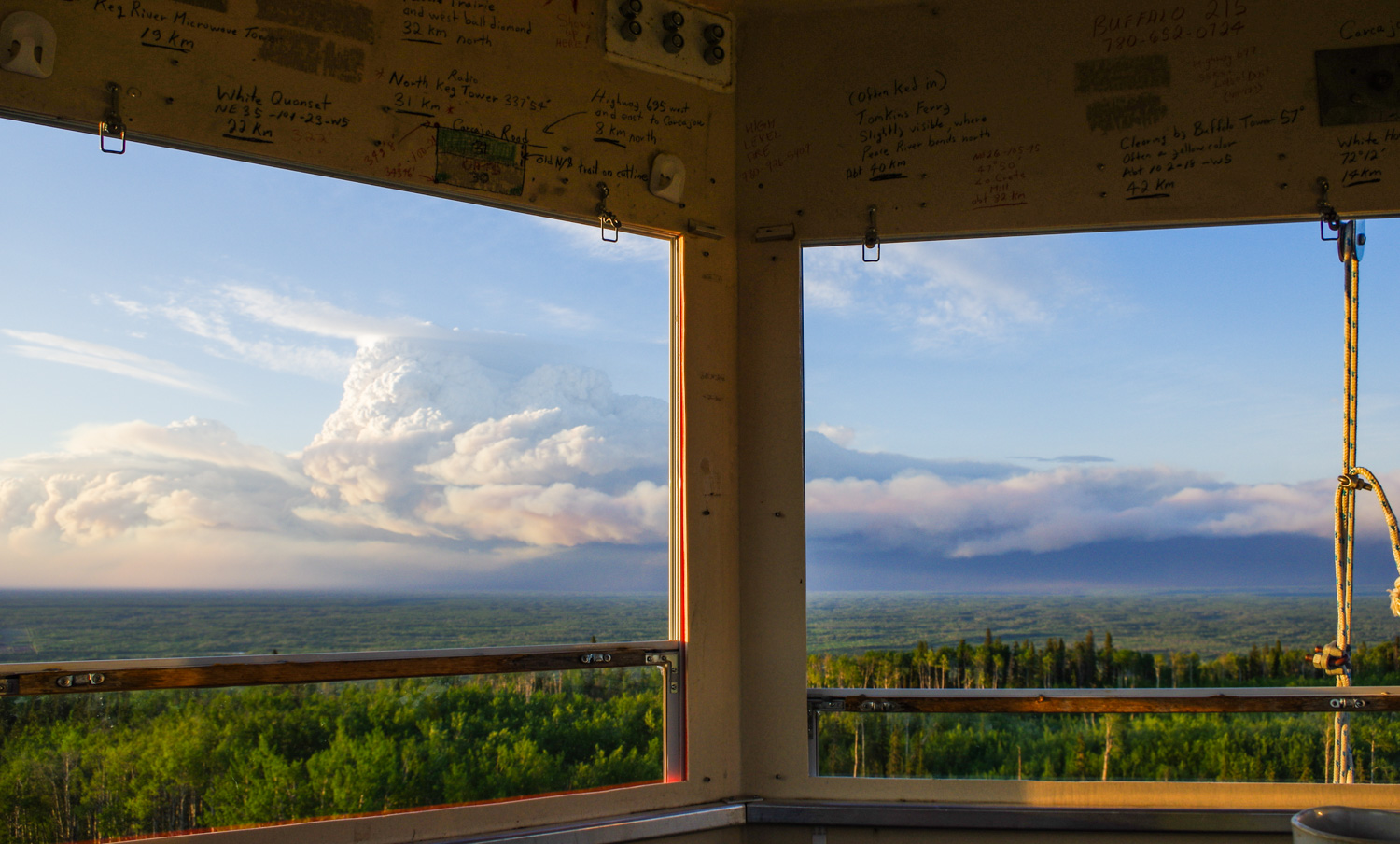

At one o’clock in the afternoon, the sun was baking the forest at 25 degrees Celsius. The wind whipped the trees back and forth. Cirrostratus, a sheer layer of high-altitude cloud, spilt across the sky like milk on a blue tablecloth. I delivered my afternoon weather report to dispatch and poured myself a cup of coffee, then placed the Thermos back on my Fire Finder, which doubled as a coffee table. The wind howled, the cupola shook, and the coffee in the Thermos sloshed back and forth. My nerves were already shot, but my eyes plodded along the horizon, scouting for smoke.

A wall of ominous yellow-and-grey smoke was advancing from two hundred kilometres away to the southwest. It wasn’t a singular smoke, rising up like a ribbon, rather, it was a curtain of smoke smothering the horizon. I became aware of the smoke in the peak heat of the day, as the source, a distant wildfire burning out of control in British Columbia, continued to edge closer. The fire already covered over two thousand hectares and was rapidly spreading into Alberta. One hectare, the measurement used in the world of wildfire, is equivalent to two football fields. I did the math. The fire was four thousand football fields. It was roughly thirty kilometres square, or the equivalent of several small towns stitched together. I couldn’t keep my eyes off the smoky substance in the distance. Part of me wanted to fly closer to the wildfire, to witness the flames torching above the tree canopy. The other part of me felt relieved that the fire was so far away—and could remain, in mind, an abstract entity.

Firefighters from our district were already waiting at the provincial border to slow the spread of the fire as several small towns in the area were at risk of being overcome. Days ago, Forestry had established a hundred-man camp for the wildfire they called ABC001. Every reported and confirmed wildfire gets a name, I was learning. ABC stood for Alberta–British Columbia. The numerals 001 denoted that it was the first cross-province fire of the 2016 season. The naming of wildfires was much more than geographical; it was political and, most importantly, economic. Who would be responsible for managing the wildfire? And who would foot the bill?

A self-portrait in the cupola

Rolling smoke in the distance

“XMA685, are you by?” the radio suddenly barked.

I jumped at the sound of my neighbour’s call sign, XMA685. His fire tower was roughly fifty kilometres to the east; we both looked out upon the Métis farming community. But who was calling? It was Channel 99, the radio frequency reserved for lookouts to discuss poten- tial smokes and get cross-bearings from their neighbours in order to gain a precise location before reporting it to dispatch. Pilots and firefighters couldn’t tune in to this frequency.

“I’m seeing smoke over the farmland to your northwest,” the mystery voice boomed over the radio.

The word smoke nearly sent my coffee flying. That’s impossible, I thought. Moments before, I had been looking north and hadn’t seen the faintest sign of smoke. I spun around and was horrified to see that there wasn’t just one smoke, there were four fucking smokes! I grabbed my binoculars off the Fire Finder and focused on the largest column. There was no mistaking the smoke column for anything else. “You’ll know smoke when you see it,” a seasoned lookout had told me before I flew out a week ago. “You’ll know it the way you know the difference between food that’s good and food that’s gone bad.”

The fires must be forty or so kilometres away. What could it be? Fires burning in a farmer’s field? Power line fires? I couldn’t think straight. The smoke gathered and rolled white, much whiter than I thought smoke could be. My hands shook as I watched it billow and expand. The largest smoke column doubled in size, rising high into the atmosphere. Later, I’d learn that the four fires were caused by sparks cast by the wheels of a train screeching along the tracks, which ignited the bone-dry dead grass. It turns out grass fires burn white, not black, and can move up to twenty-two kilometres an hour.

I knew what I needed to do—take bearings on the smokes and jump on the radio to alert dispatch—but I remained frozen in place, binoculars glued to my eye sockets. I could see a handful of farmhouses less than a couple of kilometres away from the smoke plumes. I began to panic. Was this my fault? I should’ve seen the smokes sooner. In just the minute or so I’d been captivated by the wall of smoke approaching from the south, a new fire was born to the north, and it was now escalating rapidly.

The largest column was massive now, rolling like a wild animal, rising up to a staggering height.

“26, this is XMA685 with a pre-smoke,” said a male voice over the radio. It was my neighbour, the lookout to my east, who’d worked at fire towers for more than twenty years. His voice sounded anxious as he reported his bearing and distance on the largest smoke column. “There are four smokes,” he said in a panicked voice. “And they’re coming up fast!”

The radio lit up with a cacophony of voices. The dispatcher alerted helicopters and firefighting crews stationed nearby, who went racing towards the smokes, now four thick white pillars rising into the sky. I needed to jump on the radio and pass my bearing to dispatch, but I remained paralyzed with fear.

“Confirmed wildfires,” said a crew leader from an approaching helicopter. They hadn’t even flown over the smokes yet. “We’re going to need tankers.”

Through my binoculars, I watched the air tankers drop three thousand gallons of clay retardant on the blaze. The blood-red substrate splattered against a sky of white smoke. My sense of incompetency grew as tall as the smoke columns. The fire devoured the dry grass in four long gulps. One of the smokes edged dangerously close to a farmhouse as I watched from afar, shocked. But I did nothing but stand there, watching, feeling terrified—and helpless.

It took them several hours to stop the spread of the blaze, to call the status BH, or being held. It occurred to me that no one had called to ask, “Trina, can you see the fire?” Perhaps they thought, she’s just a rookie. It’s only her second week on the job. She doesn’t have the slightest clue what she’s doing.

At 8 p.m., I pulled on my harness and descended the ladder. My breath was ragged. My self-loathing grew stronger at every rung. One hundred rungs down.

Useless.

Useless.

Useless.

Useless.

Useless.

I remembered something one of the rangers had asked me.

“The hardest part of the job has nothing to do with calling in smokes,” he said slowly. “What will you do when you’re alone with your mistakes?”

“ARGHHHHHHHHHH!” I shrieked into the wind. My own voice sounded unrecognizable. I was physically and mentally exhausted from another long day in the cupola, hot, cramped, and bored, delirious with hunger. My throat was a desert. Frustration spawned, infecting me on a cellular level. For a moment I could see myself, dangling off the ladder like a leaf on a branch. Who was this woman hanging off a hundred-foot tower, screaming as though she was coming undone? Why had they hired me? And why—

“Aroooooooooooo!”

I quickly glanced below, half expecting to see a wolf snarling up at me.

“Aroooooooooo!”

Holly tilted her snout skyward and howled up her encouragement. Hurry down, Human! she seemed to say. Her torso wiggled back and forth like a worm on the end of a hook. She looked so ridiculously happy, I couldn’t help but crack a smile. The dog had waited all day for my descent, eleven hours of sleeping curled beneath the tower and dreaming in the shade cast by the stand of pine trees. Her loyalty awed me to the bone.

Trina’s dog, Holly

Looking up from the garden

My feet touched ground and Holly danced around me gleefully. I rubbed her head, reached for one of her soft velveteen ears. She led me towards the cabin, moving with the energy of a puppy, yowling happily.

This, I thought. This is why people live with dogs. Not for protection from wolves, but protection from the viciousness of one’s own thoughts. A soft buffer against the anxiety of failure, disappointment, and being completely alone.

That evening, I patted the empty space beside me on the bed, she happily jumped up, and we slept together, soundly, offering up our regrets to the nothingness of dreams.

—

The following day, I watched the largest of the four fires, which had grown to thirty hectares in size, be reduced from a mammoth plume of white to a hazy smear on the horizon. It didn’t take the firefighting crews long to call UC, or under control, on the wildfire they’d labelled PWF034, although they’d continue to work it—unit crews spread out through the burnt remains, searching through the blackened grass and forest to douse any remaining hot spots—for several more days.

Wildfires torched the province. In Fort McMurray, the Horse River Fire continued to rage northeast, driven by the prevailing southwestern winds towards the Saskatchewan border. And still—no rain. The extraordinarily hot, dry conditions lit fear amongst managers and policy- makers. Forestry officials issued a province-wide ban on any kind of fire activity, from starting small backyard campfires to burning massive brush piles on cleared farmland. The use of ATVs—suspected to be the trigger for the Horse River Fire—was banned in recreational areas. Wildfire scientists predicted that the colossal blaze would double in size by the time it reached the Saskatchewan border. There would be no extinguishing it. Only Mother Nature could quell the hungry spread of the flames.

Until the skies opened, we’d be stuck up in the sky on extreme hazard. My stamina for these long, tiring days was fading fast. My confidence, shaky to begin with, was completely shot.

I didn’t want to pester my lookout neighbours and become that gun-shy rookie, a fly buzzing in their ears asking stupid questions. Ralph was calling me nearly every day to check in: “How are you keeping over there?” I didn’t feel I was keeping it together. I was falling apart from stress and exhaustion, riddled with anxiety that I’d miss calling in another smoke.

“I’m managing okay,” I said. “But this job—it’s more complicated than I expected.”

“It’s not a picnic out here,” he chuckled.

I called up the woman who called herself the Happy Lookout. The sound of her voice was so kind, friendly—comforting to my strained nerves. I heard myself opening up to her about my fear.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “You’re doing fine. The first year is definitely the hardest.”

Inside looking out

The Happy Lookout had worked at the same fire tower for over fifteen years. She knew the preferred routes of the black bears in the area, and the place where the forest orchids bloomed. She planted wildflowers around the cabin and grew salad greens in planters on her screened-in porch. She brought out her own water filter system to harvest the rain for drinking water, and tried to be self-sufficient and live as softly as possible on the clearing of bush where she returned every year.

The woman told me that, in her rookie season, she’d accidentally called in a “spook,” the name given to a column of moisture rising from the earth after a hard, heavy rain that looks eerily, “spookily,” like smoke.

“Then I called in another smoke. Then another. I didn’t realize they were spooks.”

A pilot flying in the area had responded on the radio, for everyone to hear, arrogantly admonishing her. “Didn’t they train you to tell the difference between smokes and spooks?” he’d asked.

She was completely humiliated. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it for days!” she said, laughing woefully.

“Here’s the difference I’ve noticed between men and women,” she said. “Men will automatically call in a smoke. But women, we’re taught to second-guess ourselves. We wait. We watch. Is it a smoke or not? We worry more about calling the shots. Women tend to doubt their own judgment.”

The key to the job, she told me gently, was to learn to trust myself. “Trust your gut,” said the Happy Lookout. “And don’t worry about making a mistake. That’s what we’re out here to do—look for smokes and call ’em in fast. Better safe than sorry.”

This story is a lightly edited excerpt of Trina’s memoir, Lookout.

Trina Moyles is a fire tower lookout and author. Her new book, Lookout: Love, Solitude, and Searching for Wildfire in the Boreal Forest, is a page-turning memoir about a young woman’s gruelling, revelatory summers working alone in a remote lookout tower and her eyewitness account of the increasingly unpredictable nature of wildfire in the Canadian north. Learn more on trinamoyles.com.

Be the first to comment