Queer Nature – Meet Co-founder Pınar Sinopoulos-Lloyd

Queer Nature

Interview with Co-Founder Pınar Sinopoulos-Lloyd

By Gale Straub

Banner image by Megan Newton

Pınar reached out to us after we collaborated with Liz Song on two podcast episodes centering around diversity, equity, and inclusion in the outdoors – and we are so glad they did. Pınar is the co-founder of “Queer Nature“, a growing Colorado-based project “dedicated to cultivating earth-based queer community through traditional skill-building.” They develop programming for LGBTQ+ and allies that deepens our relationship with the land and each other through a queer and decolonial lens.

Meet Pınar

Tell us about your entry-point to the outdoors. Where did you grow up? When did you first feel a connection with nature?

My matrilineage is Huanca, native to the Andes, as well as Chinese from Spanish slavery in now called Perú in the 17th century. My patrilineage is from the southeastern mountains of Turkey. My upbringing was split between two countries: first half in Turkey, and the second half in the Bay Area of California. My early experience as a mixed indigenous person is being “othered” in Turkey, a nationalistic country. When moving to America, I didn’t speak for half a year while being immersed in an unfamiliar language and culture. Both these experiences of being othered developed a strong observant quality in me which I now attribute as a skill of survivance to evade assimilation. The only other beings I noticed with a similar experience of situational awareness were nonhuman animals. I began to empathize deeply at first with animals and then extended out to plants, trees, rain, mountains and creeks.

Growing up with an immigrant father who lived in poverty in rural pastoral Turkey, he did not emphasize much on outdoor recreation for neither me nor my sister. My initiation into nature connection was through deep bonds with animals who I felt a rooted solidarity with rather than competitive and fast-paced sports or activities. This greatly informed the way in which I related to other natural beings. Nature was never the backdrop to an experience, but rather the one who I was met by. My more-than-human relationships initiated a profound romance with the natural world which was the first place I felt I belonged.

Pınar in their element; Photo by Megan Newton

How do you define “queer”?

This is a great question. This word has a complexity to it almost like an entire ecosystem of queerness. I love the poet, Brandon Wint’s, words on queerness: “Not queer like gay. Queer like, escaping definition. Queer like some sort of fluidity and limitlessness at once. Queer like a freedom too strange to be conquered. Queer like the fearlessness to imagine what love can look like…and pursue it.” This is applicable to gender and sexual orientation. I would also add that queerness is a landscape. My experience of genderfluidity is like a expanding landscape of my soul in relation to the natural world.

As an indigenous queer, it also has a subversive element to it that is life-giving liken to a trickster who flips perspectives of normativity. I also cannot talk about queerness without speaking about my queer lineage of Quariwarmi–Andean “two-spirit” sibling. From my ancestry, the Incan cosmology is centered around an androgynous creative force. The third gender ceremonialists, Quariwarmis, represented the liminal spaces that held together our cultural story as a people. Queer is akin to decolonizing structures in a way that gives back to Pachamama and reestablishes a balance that in-between medicine can offer.

Why did you feel less drawn to urban queer culture growing up?

When I share that my adolescence as a queer youth was in the Bay Area, more often than not, people assume I was culturally met there. I definitely had the privilege of not batting an eye when I held my partner’s hands or kissed in public. But I was not the teen involved in my high school’s Gay Straight Alliance (GSA) or seeking out queer spaces. You would more often find me taking pictures of the subtleties of the natural world.

In my body, I knew I belonged to the natural world rather than the urban queer communities. At the time–and arguably currently–the queer culture was centered around partying and drinking in an urban wilderness finding refuge with one another. I found refuge in the colors of the autumn leaves, my connection to my neighboring squirrels, and what they reflected in me which was my own wildness and ecologically/ancestrally informed queerness.

In hindsight, I see this is due to being an indigenous queer person who was isolated within a predominantly white LGBT community. That these urban centers stood on indigenous land who had and continue to have their own gender and sexual diversity which is greatly impacted by colonization. Growing up in unceded Ohlone territory, I felt my more-than-human community was exposing the cultural wounds that impacted my own ancestors. In the natural world, I undoubtedly belonged and that is a revolutionary feeling for a queer/trans mixed-indigenous person who was struggling with my very existence.

What are the benefits of LGBTQ+ coming together in the wild?

The work of Queer Nature is rooted in practices of belonging through naturalist knowledge, wilderness skills, awareness arts, natural crafts, and council. This is also coupled with knowledge of the cultural history of the land we connect to and the exploration of our own ancestral roots. There is rarely cultural access to “outdoor recreation” for the LGBTQIAP+ community. As a nonbinary/trans person, boy scouts or girl scouts may have never been a safe place to be yourself. The wilderness skills world tends to be an intimidating environment dominated by white cis-males who are often competitive and do not emphasize relationship to land. In a lot of ways, colonial mentality infuses the outdoor fields which mirror a kind of “conquering.”

Queer people who grew up rurally tend to move to the cities to find safety with other queers. This is especially true for queer and trans people of color (QTPOC) who are far more often impacted by hate crimes. As a project, we emphasize an intersectional lens of oppression and liberation. Since colonization, the queer community has become urbanized and removed from the land to find refuge to live their lives. We also recognize that there have been particular traumas to gender-variant First Nations of Turtle Island in particular. This has been a devastating severance. Queerness is a dream of the earth. It is a land-informed fruition across the globe; an ecological formation. We have held integral cultural roles within those communities similar to having our ecological niche within our ancestral systems. Some of these roles have been midwives, counselors, healers, shamans, ceremonialists, cultural storytellers, artists and warriors. Queerness is ancient and the narrative that we are a new cultural phenomena is harmful. To bring us back to the land to reclaim and understand our cultural and ecological roles is core to our mission. To reconnect us to our earthy queerness is an act of resistance in a dominant culture that says we are unnatural and do not belong. This is about belonging in a deep way.

Bringing queers into the wild is a way to challenge these erasing narratives of gender binary, of our “unsafety” outside, an extraction-based view of the earth and that we are “unnatural.” It is us unearthing ancient roles that are passed through our lineages and hybridizing it with what it means queer in this world now. We birth culture in a particular and necessary way.

Bringing queers into the wild is a way to challenge these erasing narratives of gender binary, of our “unsafety” outside, an extraction-based view of the earth and that we are “unnatural.”

In my Quariwarmi tradition, the androgynous space was pivotal during a cataclysmic change. The ones who were occupy the liminal space were the ones who were consulted with. I am curious what force an earth-based queerness would be as originally intended. Nature mirrors us our gift in the world which is inherently unsettling to the ecocidal culture at place. Bringing queers out into the wilderness begins a process of cultural and individual healing.

When did you and your partner start Queer Nature? What was the catalyst for its inception?

As I began to study ancestral skills–an alternative term for survival skills, I felt out of place wherever I went to learn. This was for several reasons. I was usually the only indigenous and/or person of color in the space, and I was more often than not the only nonbinary person. As an indigenous person, I would often be exotified since we were learning “primitive skills” that the “Indians” ”did” which ironically enforced the erasure of our existence. As a nonbinary person, I was often erased since the “wilderness skills” culture amplifies the gender binary.

In 2011, I was invited to go to this free gathering specifically for trans/women folk to learn ancestral skills (since it is invitation-only, I will not disclose the name). This was an empowering space where we read academic papers on decolonization every morning around the fire. After this weekend, I realized I wanted to create spaces for queer and trans folks to learn out on the land in a culturally accessible and relevant way. I also knew I wanted to offer vision fasts or wilderness solos for the LGBTQIAP+ population to support their radical becoming into the world. As I continued to reskill myself, the need to create a space that was so often absent for me became apparent.

In 2013, I met my spouse, So, who was visiting Wilderness Awareness School where I was attending their Anake Outdoor School. Our encounter was an unexpectedly powerful one that left me bewildered and empowered. So was the first person I met who also had a similar mystical connection to the natural world that was informed by their* queerness (*gender-neutral pronouns). They had a tattoo of “earthling” tattooed across their chest in Old English font that marked their belonging.

So and Pınar

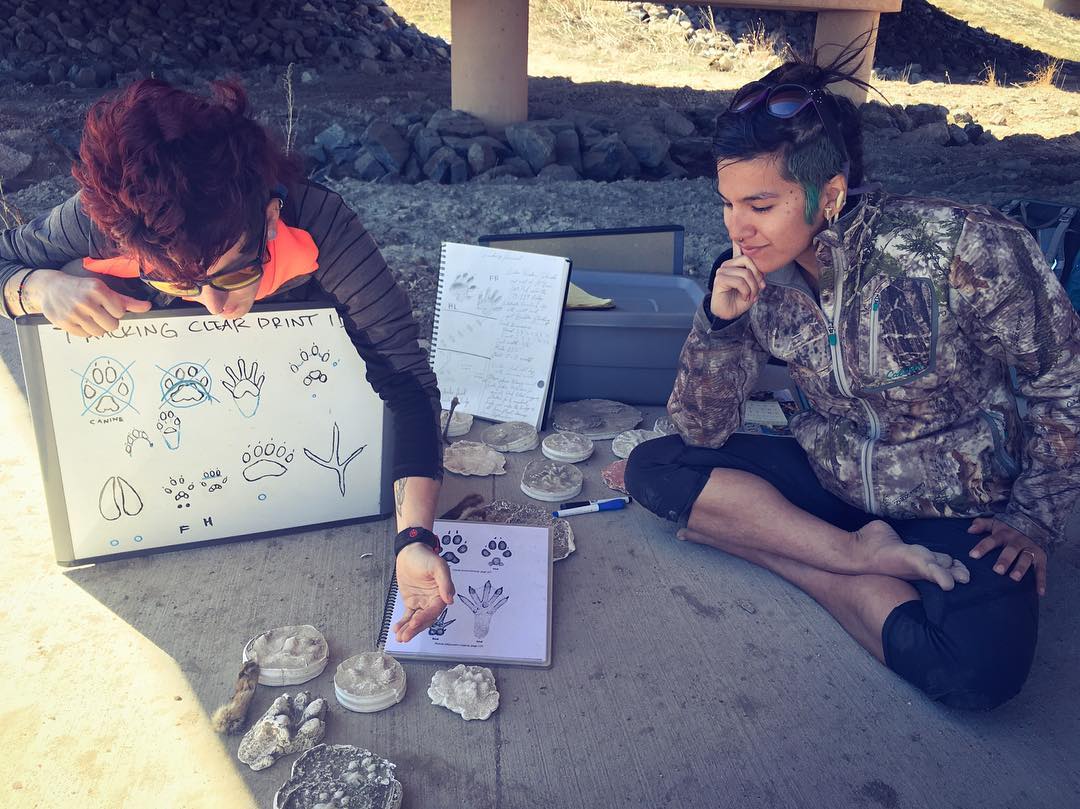

We fell in love in the Cascadian woods where Wilderness Awareness School is nestled. As we went tracking together and shared our mystical connections to the natural world, we began to see many possibilities emerging from what we could bring together in service to the world. We continued to reskill ourselves and during the process moved to to Colorado where we are now.

In the summer of 2015, we participated in the School of Lost Borders’ Queer Quest which is a vision fast for the LGBTQIAP+ community. Being in ceremony with queers was a first for me and this experience was foundational to further inspiring So and me to be of service to the queer community. We both had our individual wilderness solo experience in the high aspen forests near Buena Vista, CO. This was the second fast in which I went out to pray on the land asking how to be of service in this ecocidal culture and how to remediate cultural trauma. The conversations with the land were potent and informed the fruition of Queer Nature. The witnessing of the other queer folk in ceremony motivated us to continue creating space where earth-based queer magic can happen.

A few weeks after the Queer Quest, we ran into my friend, Emily Isaacs, the then new executive director of The Women’s Wilderness Institute at the climbing gym. She had been reading and hearing our perspective via Facebook and asked if we wanted to run a program for queer youth! This was the catalyst of a project of Queer Nature that mobilized us. We soon got feedback at Boulder Pride that there was a lot of interest from queer adults, so we ended up changing the program a bit to what it is now: for the LGBTQIAP+ community that is 16+ years old.

In spring of 2016, we received a grant from the Open Door Fund to run sliding-scale programs for the LGBTQIAP+ community. People can register for these subsidized programs for $10 with a sliding scale of $10-$35 to also make it financially accessible. Since survival shows have become popularized, survival skills has become a boutique offering that often is a financial barrier for folks who want to reskill themselves. The rate of unemployment for trans and gender nonconforming folks is significantly higher which is what motivated us to address this financial barrier.

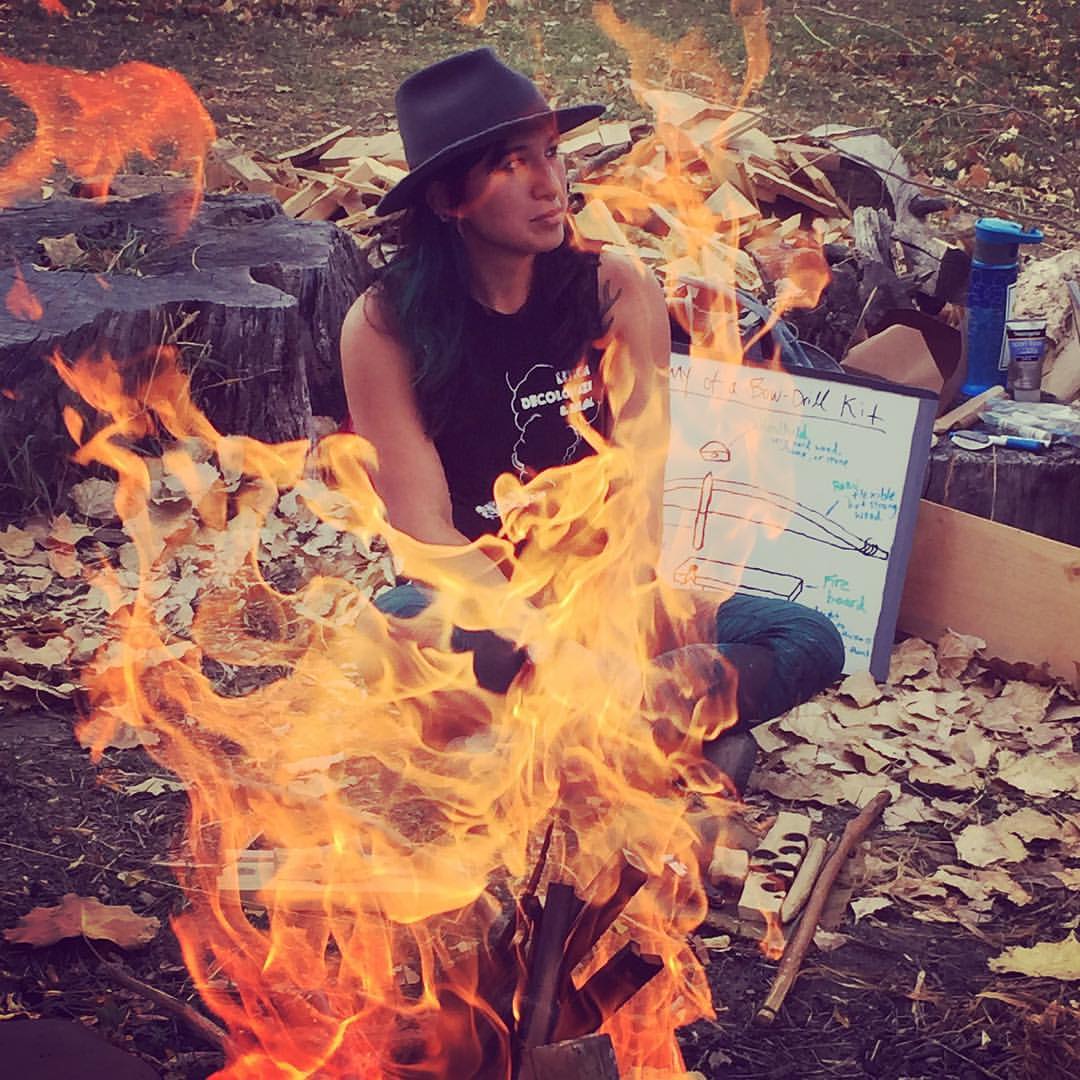

Photo by Megan Newton

What are your partner’s strengths? How do you complement each other?

So is an incredibly articulate wordsmith. They are skilled in didactic mentoring in composing and sharing information about whatever we are teaching. They tend to take a lead role in speaking due to their natural ability as a sustained speaker in front of a group.

As for myself, one of the first things I do at every Queer Nature skillshare is share whose land we are on, which is unceded Arapaho, Ute and Cheyenne territory. I share about Valmont Butte, which is an iconic land formation that is a traditional burial ground as well as hunting grounds for the First Nations people. I share how this butte has been mined for over 150 years since the settlers arrived. This foundation begins an invitation to consider how we engage with the land we occupy.

As far as my mentoring, I take more of a relational and personal approach to mentoring. This looks like going up to individuals while working on making their bowdrill kits and asking how their process is going and what is coming up for them. It looks like tracking each person’s passion and attempting to connecting it out on the field by engaging them in questions.

Our other team member, Jessica Dallman, is a wilderness therapist. Their strength is to track the emotional landscape and ask questions during our closing that weave a personal and sometimes communal experience. They also have the skills to address overwhelming emotions that emerge while practicing ancestral skills all together. With their strong awareness around social positions of power and oppression, they are also able to navigate intersectionality and amplify voices.

So and I complement each other in the ways we teach since I can take a more vocal and lead role if needed, yet this is not necessarily my tendency. My mentoring style thrives on one-on-one encounters where I can encourage the individual’s process and push their skills. I also love to meet people where they are at on a psychospiritual level since I believe these skills can unearth stored ancestral emotions through our body. So has the exquisite skill of geekery and information that is incredibly valuable leaving students empowered with knowledge. Jessica’s skill on the emotional terrain has similarities to mine, yet when they hold this role as their main role, it supports me as a mentor to focus on teaching the physical skill. Jessica’s ability to read the group field is an incredible asset since it supports us to mentor more empathically, and therefore, effectively.

Your mission states “we believe that the more we discover about ecology and our place within it, the more we can grow our definitions of solidarity, allyship, and humanity, while also growing our inner resources for personal resiliency.” Why do you believe this to be true?

Nature is the source of resiliency and can be a mirror to ourselves. When we immerse ourselves in noticing the subtleties we glanced by and ignite our wild curiosity again, we are able to be present to the mirroring nature can provide of our own resilience. We can realize our own stories of survival and the awareness that developed post-trauma. This builds on our own inner resources for healing and resiliency within our internal landscape.

I will share a caveat that the natural world’s sole job is not to mirror us for our own benefit. The natural world is an interdependent organism in which we are connected to, and therefore, we inform one another. It can be dangerous when we get into the terrain of solipsism where the natural world only exists to benefit us. The natural world beckons us to become fully ourselves is a gift back to the world since when we realize what Arne Næss refers to as the Ecological Self, we begin to unravel our complacency to an ecocidal culture. This is where reciprocity comes in within the relationship with nature.

As we begin to track patterns on the landscape and get to know individual stories of wild ones around us, we can begin to see our impact in the interconnectedness of life within our human sphere and extending out to our more-than-human community. Tracking is reading interdependency since we see that every entity impacts one another by sometimes pulling and pushing them across the landscape. Everyone is somehow autonomous yet interdependent at once in a weaved collective story of survivance and evolution.

As we begin to track patterns on the landscape and get to know individual stories of wild ones around us, we can begin to see our impact in the interconnectedness of life within our human sphere and extending out to our more-than-human community.

As one begins to experience empathy to their ecological kin in their bioregion, this builds the foundation for interspecies solidarity. It has the potential to mirror how we can leverage our own impact in the world and shift the trails we take. Getting to intimately know your ecosystem can provide an invitation to assess our own ecological and cultural role. When we see that everything has a place in nature, it begins to highlight our own placement (or displacement), and begin the sometimes unsettling conversation of embodying our own ecological niche.

To be fully human is to fully inhabit our Ecological Self. With this comes a shattering empathy for entire bioregions engaging us to step into action in solidarity with our human community as well as our ecological community.

Tell us about the types of services you offer. Are these limited to the Colorado area?

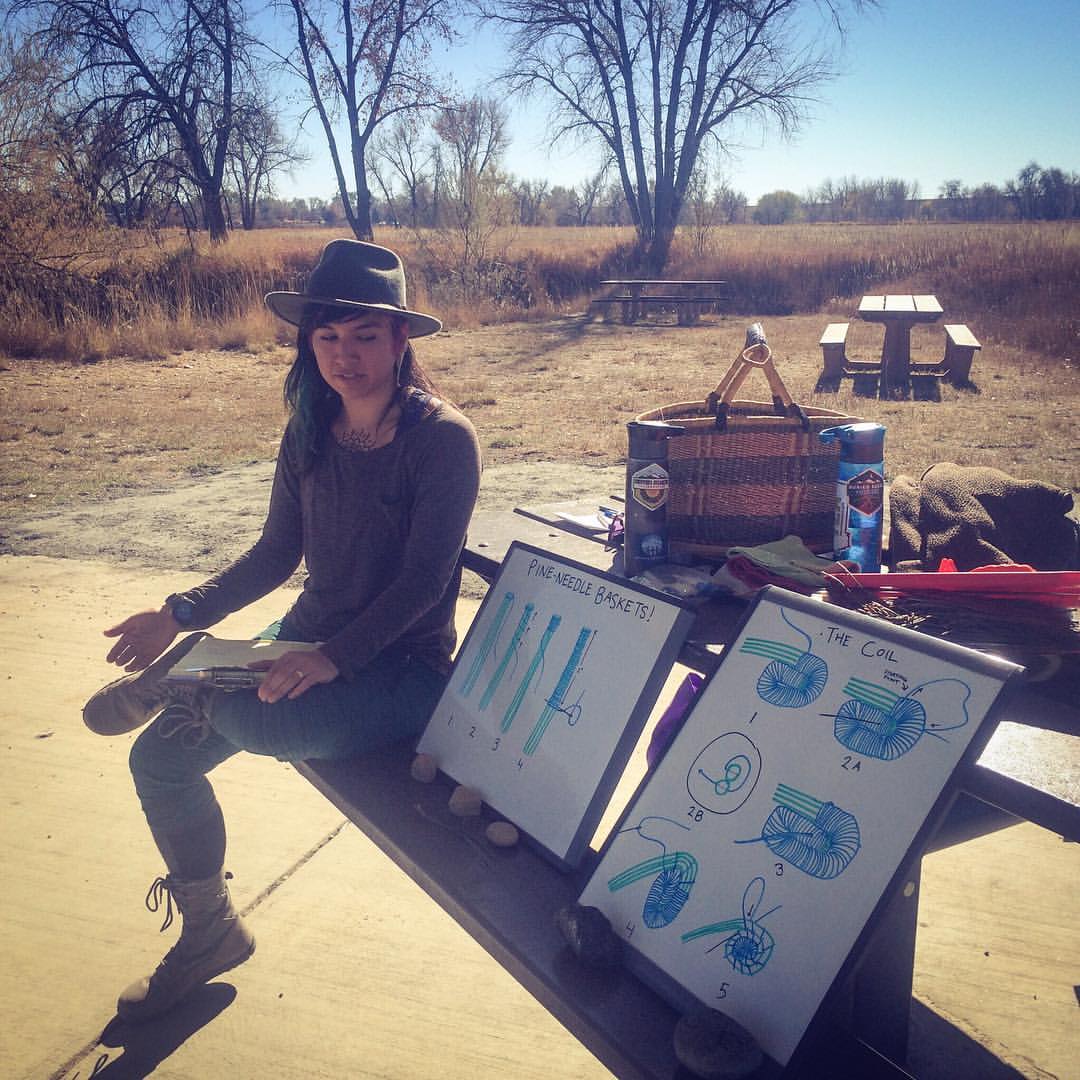

Through the Open Door Fund grant as well as donors, we have been offering sliding-scale skillshares teaching friction fire, wildlife tracking, pine-needle basketry and future ones such as herbal medicine, equine connection & self defense and intro to botany. We make these skillshares financially accessible to address a barrier to the outdoors for marginalized populations. All of our skillshares have had waitlists so we are applying for more funding and requesting more donations to fund more skillshares to keep up with the demand.

We have been partnering with non-profit organizations such as Women’s Wilderness teaching Nature Awareness courses to allies; Youth Passageways being a member of the Cross Cultural Protocols, co-designing a webinar on gender in rites of passage work, and developing consultation work; and Wilderness Awareness School offering a Queer Nature weekend intensive as well as a weekend workshop on privilege and power in the outdoors both in October 2017. We also co-guide vision fasts with the School of Lost Borders for LGBTQIAP+ youth (Queer Youth Quest) as well as canoe-based vision fasts through The River’s Path for female-identified folks.

We do not exclusively work with the LGBTQIAP+ people since we also feel that our role is in-between folks is to strengthen the bridge between populations and to empower others who also have not felt welcomed into nature-connection and ancestral skills.

For the summer of 2018, we are planning to fund a multi-day backpacking trip in Wyoming and a multi-day canoe trip in Utah in addition to our community skillshares for the LGBTQIAP+ community. We are not limited to Colorado and are open to collaborations and inquiries.

Explain how “Queer Nature” folds in the cultural history of land in the United States into its curriculum. Why is this important?

A startling absence within the wilderness fields is the lack of integrating indigenous history as well as current indigenous struggles. My experience delving in nature connection was this was an integral aspect of nature connection. This is in part because I learned tracking at Black Mesa where I was shepherding for a Diné elder. Every morning, she would wake up and walk outside her hogan, tradition Diné structure, and read the tracks on the landscape as if a newspaper. She has always been a foundational aspect of my journey to reskilling and someone who cracked upon my awareness to ancestral contexts and land-stored trauma liken to how trauma stores in our own bodies.

In nature connection, we fall in love with the land and become curious of its inhabitants. We research who is native and who is an invasive species to understand the complexity of the place. Naturally, this leads to wanting to know who tended the land for time immemorial. Who evolved with this land and has been formed and has formed this bioregion? When we begin our journey toward nature connection, it must include this, because this erasure is harmful. Even the concept of “wilderness” erases indigenous history and presence since it implies that humans have not and do not occupy it. The formation of national parks to create a “pristine wilderness” required the removal of native people. John Muir, the “Father of National Parks” and founder of the Sierra Club, wrote terribly racist remarks about the native populations and enforced the removal of them as he pioneers what we know as “wilderness” today. It is imperative to know what was (and is) required to maintain the concept of wilderness. When you uproot an earth-based culture that has evolved with the land for time immemorial, the trauma is immense not only to the people, but also to their more-than-human community.

If we see ourselves as animals, we must acknowledge the trauma of the land as a part of natural history rather than othering ourselves from the story. It can be uncomfortable to learn this history since it is unresolved. It can bring up questions that one grapples with for sometime init iating a research into one’s own ancestry and the tracks their ancestors left on the land. These are worthy questions to wrestle with and can create a deeper sense of accountability to become an honorable ancestor to the future generations (human and more-than-human).

iating a research into one’s own ancestry and the tracks their ancestors left on the land. These are worthy questions to wrestle with and can create a deeper sense of accountability to become an honorable ancestor to the future generations (human and more-than-human).

Cultural remediation is integral to developing sustainable ways of living. The dominant culture evades and erases trauma. It is our individual part to begin leaning into that trauma and figuring out what reconciliation may look like on the lands we connect to. A question I continually ask myself is how to be an honorable ancestor for my ecological communities. As an indigenous person, cultural history is ecological history and the separation between them perpetuates amnesia that is harmful for everyone.

Looking forward, what are you most excited about over the next few months?

We are so excited to run the first Queer Youth Quest through the School of Lost Borders! As I mentioned, So and I were participants of the Queer Quest for adults in 2015 so to be guiding the first youth one this summer is such an honor. A few of the participants will be QTPOC youth–including my own sibling–which immensely inspires me since my experience as a QTPOC youth was incredibly challenging. To be able to support these queer and trans teens is such a gift. Every time we guide and/or mentor, it is one of the most nourishing experiences. It is a practice of falling in love with people through their stories and becoming a temporary ecological community together.

Collaborations are always inspiring to us. A part of our goal at Queer Nature is to empower the LGBTQIAP+ community in many ways. One way is hire on queer guest instructors to share what they love to their community and to further decentralize skills. We are working with two powerful herbalists in our coming skillshares as well as a horseperson and a self-defense teacher. Amplifying queer voices and skills is an integral aspect of Queer Nature.

Getting to collaborate with Wilderness Awareness School for a weekend intensive next fall is something we are looking forward to as well. Being invited back to the place where So and I met to give back to that community is an honor. Anytime we have a chance to be outside with other folks, we are stoked! There is much to look forward to as Queer Nature continues to grow.

Photos courtesy of Queer Nature

This is a stunningly beautiful article that forces one, queer or not, to dig deeply into their understanding of the natural world and how that understanding has been shaped by the dominant culture. I look forward to reading this again and again to fully absorb all of its wisdom. Thank you for interviewing Queer Nature!

This is such a rich and important conversation. Thank you for welcoming this story and leaving us lingering with imperative questions, especially about inclusivity outdoors and reciprocity.

Oh! this speaks to me. Thank you. <3

This album contains tunes about queer ecology, love, gay rights and heterosexism. Check out When Heterosexuals Rule the World, Lions, Bison Dragonflies and Swans, (all species with homosexuality, ) Get Out of Town, ( about climate refugees,) Cornflakes, (about climate change and overpopulation, ) and others for your listening pleasure.

https://pinkjimmieonapalebluedot.bandcamp.com/releases