Interview With Leigh Ann Henion

Interview With Leigh Ann Henion

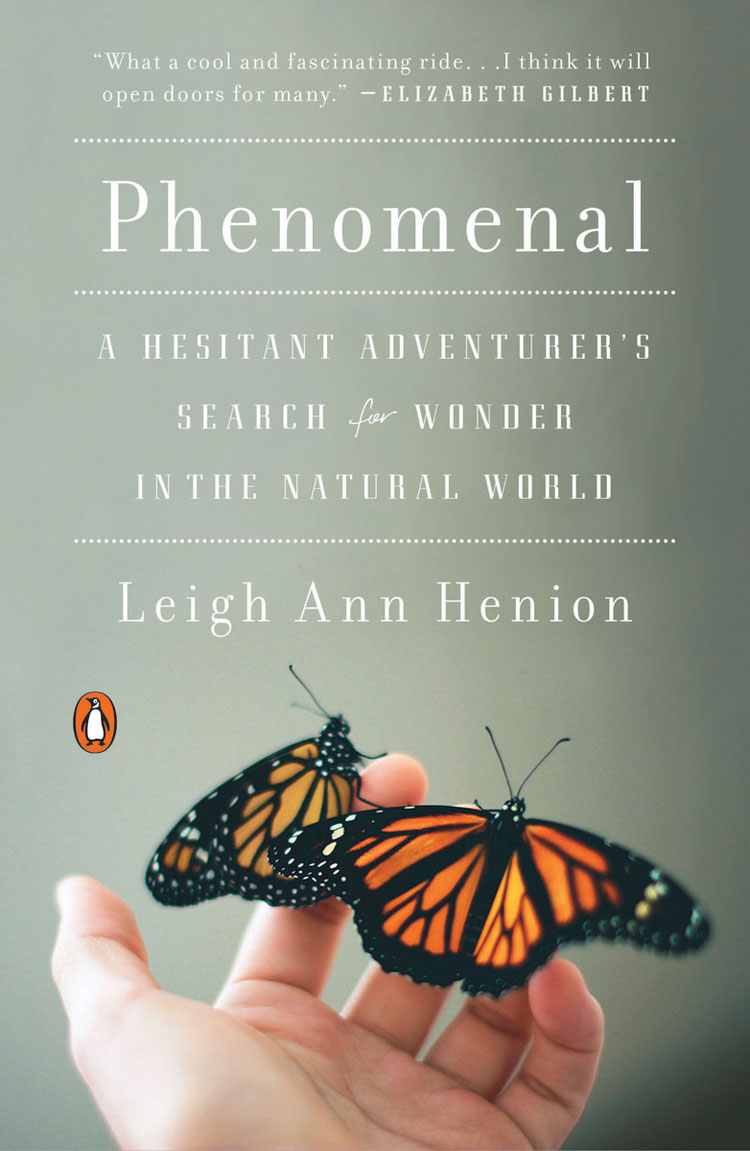

Author of the book “Phenomenal: A Hesitant Adventurer’s Search for Wonder in the Natural World”

Interview by Gale Straub, photos by Leigh Ann Henion

Leigh Ann Henion went on a personal expedition that took her around the world in search of wonder in the natural world. She describes the experience in moving detail in her book “Phenomenal.” While we read the book as an adventure memoir, there is another layer: adventuring as a mother. But should that be the focus?

Leigh Ann aptly writes, “Wonder isn’t about finding answers; it’s about becoming more comfortable with questions.”

Meet Leigh Ann

Why do you think women don’t talk about the struggles of motherhood more?

When people call me brave, in relation to Phenomenal, they’re almost never talking about how I stared down a lion, swam with sharks, or climbed a mountain to witness millions of monarch butterflies in flight. They’re almost always talking about how, in chapter one—before the story starts in earnest—I share some of the raw and difficult postpartum experience that set me on a pilgrimage to wonder.

Recently, I heard a woman call herself “a selfish mother” because she jogs regularly and goes out to eat with her husband once a week. I think, in popular culture, when a mother is noticed doing anything outside of directly caring for her family, it’s considered selfish on some level. Despite the great variation of personality, interests, and passions every mother brings to the role, there seems to be little room for variation in terms of social acceptability. I think that’s why mothers are reluctant to talk about the struggles, particularly as they relate to outside interests.

My proclivities as a travel writer presented some early challenges. But, really, anyone who pursues something atypical—regardless of maternal status—is opening herself to this sort of naysaying: Who do you think you are, trying to make it as an artist? Who do you think you are, traveling all the time? Who do you think you are to pursue “dreams?” I think creative work, or anything focused on making us emotionally better off, rather than more financially solvent, is considered a somewhat frivolous pursuit. That says a lot about what we, as a culture, value.

A scene from the Torne River in northern Sweden, where Leigh Ann traveled in search of the northern lights.

Have you found that sharing your story has opened up a conversation around attachment and parenting?

Chasing eclipses, auroras, migrations, and other natural phenomena around the globe is in alignment with the interests I’ve had and the travels I’ve taken throughout my life. But it’s not in alignment with cultural norms—especially for a mother. Make a list of all the nature, travel, and adventure books you can think of written by men who are fathers. (Questions of paternal status often require some Googling!) Then, list nature, travel, and adventure books written by women who were, at the time of fieldwork and writing, mothers. (Maternal status is usually common knowledge!) The messages I get from women who tell me they feel less alone or inspired to pursue their calling because of Phenomenal make me feel like my vulnerability has the potential to make a difference in some small way. Phenomenal is actually filed under Religion & Philosophy, and the Library of Congress categorized the book as “Women shamans—Biography.” (Still not sure what to make of that!) I hope Phenomenal will start conversations about a variety of topics—including limited perceptions of motherhood.

Would you call your postpartum feeling something like homesickness for yourself?

Now available in paperback through Penguin Press.

That’s a beautiful description. Home—my actual house—had been transformed into a disorienting, foreign place. I’d arrived physically eviscerated, and I did not speak the language. I’d been living abstractly, as a writer, and I was suddenly part of the visceral world, as a mother. The word phenomenal is defined as that which is magnificent. It also means that which is directly observable to the senses. Before I embarked on my Phenomenal pilgrimage, I had not realized how much I’d been depending on experts to interpret the world around me. In particular, I recall an incident in the Arctic, where I was worried about the thickness of some river ice. I was looking for manmade signs or reports that would assure me that the thickness had been approved for travel by authorities. But there weren’t any. When I asked a local—who clearly thought I was a little slow—I was told that, if I wanted to know how thick the ice was, I should go check it. I was asking questions that no one could answer from afar. They were specific to my location.

I think, on some level, that’s related to what I felt when my son was a newborn: No matter how many parenting books I read, they couldn’t tell me exactly what to do in my intimate situation, with my unique child, to meet his personal needs. I was on my own, and I knew it, and it was scary. Part of my journey—around the world and as a parent—has been learning to better trust my instincts and experiential knowledge. It’s something that extends to another interest I developed in myPhenomenal travels: What anthropologists sometimes refer to as “other ways of knowing.” Indigenous cultures around the world have millennia of observed knowledge—about volcanic eruptions and all sorts of other events—readily available in the form of chants and stories. But, because that knowledge has been gained outside of categorically objective processes, much of that wisdom is untapped and imperiled.

Leigh Ann (right/center) and Johanna Huuva, a female reindeer herder featured in Phenomenal.

You decided to visit 7 fantastic places around the world “in search of wonder in the natural world.” Do you think you could have taken your son, Archer, with you? Do you think your outlook, post traveling, would have differed?

Every member of my immediate family has, in his or her own way, told me that they feel like their own lives have improved as a result of Phenomenal. It all happened the way it needed to, in the context of our lives. We’re in a different place from where we were when I started writing the book. It’s a better place. And the journey taken inPhenomenal, exactly as it went, got us here. So it’s difficult to question it.

On your way to Tanzania, you felt an acute homesickness. How did that feeling differ from before your travels? How did you move beyond it to appreciate the journey?

Tanzania was toward the end of my overarching journey, and it was scheduled not long after I’d returned from Sweden. It was nearly time to take the magnitude of what I’d witnessed, fully apply it to my day-to-day, and put it on paper. I moved beyond that homesickness because—as with a lot of emotional challenges in life, including my postpartum experience—the only way out of it was through it. I had a lot of wonderful teachers on that trip: a woodcarver who talked about finding solace in the Great Migration’s reliable cycles, a safari guide who’d observed a fear of death in guests’ unwillingness to watch lions feeding in the Serengeti. There was a lot to appreciate, and meditate on, about that leg of the journey.

Why do you think we often lose our sense of wonder as we grow older? Do you ever miss being a kid?

In Abisko, Sweden, chairlifts give visitors the sensation of flying through the northern lights.

New research shows that feelings of awe have the potential to make people less impatient and increasingly satisfied with life.

Of the phenomena that you witnessed, which was most beautiful?

Monarchs in flight over their ancestral homeland.

All the phenomena were beautiful in their own way, so it’s hard to hand out that superlative. But my experience with a hula school, in Hawai‘i—where a group of women and girls introduced me to a volcano-residing fire goddess—may have been the most personally transformative. The dancers’ worldviews were intimately informed by nature-based spirituality and, through them, so was mine. Volcanic phenomena and related Hawaiian tradition gave me glimpses of mind, body, and spirit integrating on a communal level.

Do you have any tips for women to see and appreciate the feeling of nature close to home?

Zebra arrive in Tanzania as part of the Serengeti’s Great Migration.

What’s next? Does that restless feeling ever go away? Would you want it to?

I haven’t done much traveling since I got back from my Phenomenal journey, and I’ve been far from restless! But, lately, I’ve been having some twinges. In my life, I find that’s how it works. Restlessness surges when I need perspective. It reminds me to pay attention. It shakes me out of doldrums, pushes me to do things that I am—at the outset—not entirely sure I’m capable of doing (hence the word “hesitant” in my book’s subtitle). Travel is a tonic, taken as needed.

Right now [end of February 2016] , I’m getting ready to head out a backpacking trip through desert backcountry with my husband and son, now six. I have never been backpacking before. My son is hoping there’s room for his teddy bear. A friend just asked if we’ve been hiking to get used to our packs. We have not. We leave in a week. I asked her if the adventure we were about to embark on sounded crazy. “Yes,” she said. “But you’ve done crazier.” Off we go, into the unknown, together!

Keep up with Leigh Ann Henion through her social media sites below and be sure to check out her book for yourself—

Editor’s Note: This article includes Amazon Affiliate links, which provide a small commission for She Explores at no charge to you. Learn more here.

[…] an interview with Leigh Ann Henion on […]

[…] an interview with Leigh Ann Henion on […]