Emotion and Experience

Emotion & Experience

Or What Will Save the Environment

By Haley Littleton

Amo: Volo ut sis

I love you: I want you to be

— Quotation attributed to Augustine by Heidegger in a letter to Hannah Arendt

I.

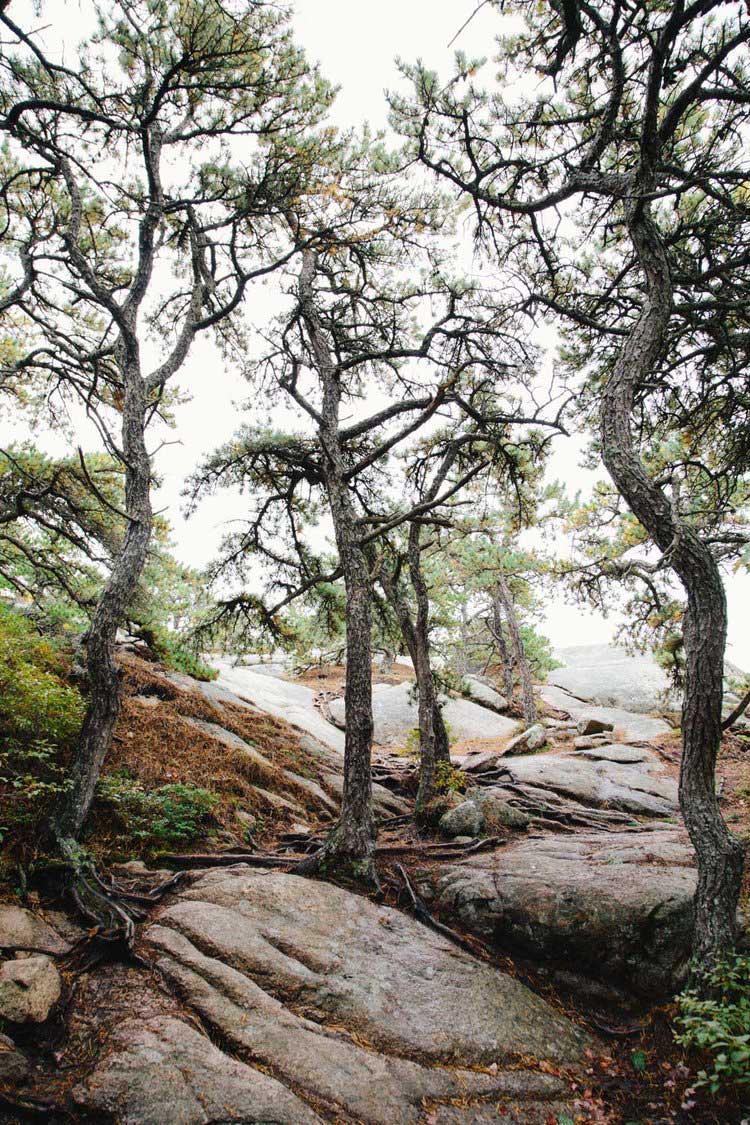

I look out over the plateau towards the display of the season’s change highlighted in deep greens, orange marmalade, and burnt red haze in the openness below. I feel the momentary onrush of affectation; it sits lodged in the back of my throat with the pulsation of emotion. I am inclined to use one word: love.

I look out over the plateau towards the display of the season’s change highlighted in deep greens, orange marmalade, and burnt red haze in the openness below. I feel the momentary onrush of affectation; it sits lodged in the back of my throat with the pulsation of emotion. I am inclined to use one word: love.

We return, again and again, in the landscapes we exist in, to love.

Amo: Volo ut sis. Love as the affirmation of being, Augustine might be translated to say, or love that gives itself and the object shared existence. Love as the power of assertion, to look across a brazenly golden valley and declare: I love this, which says something about the speaker’s emotion and the object that it is placed upon. The greatest assertion: I love you and I want (desire) that you be. In other words: I wish for you to exist purely because of this felt emotion or connection.

This does not mean, “I want to have or own you” or “I want to rule you.” It is simply: I love you, and I am happy that you merely exist. Hannah Arendt wrote that this was the basis of incalculable, grace-driven love. When applied to people, it is the notion that one need not earn the love given to them. When applied to nature, it is the impetus to love solely because the sun shines on us, the ground offers up food, and the river gives us water without asking for anything in return, as if the mere beauty of it all were not enough. Nature opens up its spaces for us to play within, climb on, ski down, or dart along its waterways. In return, we look upon it with love, happy for its existence.

We may care for our environment in order to ensure our general existence, and environmentalists can sway us by the calculated data of our lessening chances of survival, but what about love, something deeper than solely utilitarian assurance? Isn’t this what we began with? How is love a framework for environmental involvement?

How is love a framework for environmental involvement?

“People exploit what they have merely concluded to be of value, but they defend what they love,” Wendell Berry sagely wrote. We have learned to discredit our emotions in the defense of the logical or political but in doing so perhaps we displace the heart of the issue. We want nature to exist because, simply, we love it. It makes us feel things. This is where we all started, isn’t it? Of course, we get to the point where mountains are gulley runs to be tackled, traverses offer their jagged edges to be climbed, and rivers are there to be navigated, but this sense of conquering must stem from a deep appreciation for the landscape that presents itself.

The moment I can pinpoint where I most vividly first felt a deep onrush of emotion for nature was my first backpacking trip to Bill Moore Lake, in Empire, Colorado, when I was a freshman in college (certainly a late bloomer growing up in the South). Four of us women stretched ourselves around the fire, sprawled out on our backs, as the sky blinked above us and the gentle early September wind lipped at our collars. Overwhelmed by a sense of gratefulness for the stillness and connectedness I felt in that moment, I was tempted to shout or cry or hug one of my companions or release this emotion in some way. I loved it, in the least cliché way that I might use that word. I cared deeply that it existed.

II.

The emotional connection we garner from the edge of a crevice or the dense canopy of redwoods is predicated upon something else: experience.

If love is to be stimulated in outdoor spaces, the experience we have in these spaces is what comes before: to get out into the environment in which you are a part of. It is hard to love what you have never gotten to know: to come up close to the landscape, to feel it in your legs, smell it and breathe it in deeply, to wriggle toes in the sand/soil/moss.

In terms of the urban, 19th century French literary culture offers up the “flaneur,” a concept conceived by Baudelaire and further explored by Walter Benjamin. The flaneur is a wanderer in urban spaces, a passionate and attentive stroller who is happily obliged to embrace distractions, rabbit holes, and stops along the way. The flaneur drifts through the city attentive to its myriad of images, people, and tactile senses. In Baudelaire’s mind, the flaneur was the reporter of modern culture and an instrument of analyzing engagement in culture: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Writers like Bijan Stephen have suggested a revival of the idea to fight artificial busyness and its stress: walking more, stopping in little shops along the way to examine trinkets, and never rushing to get to the destination.

But what is a “flaneur” outside the city? Does the mindset translate?

It is well known that poet Mary Oliver would stroll in nature and write as she went along. Oliver was a passionate and attentive observer, even to the smallest grasshopper that landed on her plate to graze upon the leftovers. There is something about wandering, walking, hiking, or any form of engagement in nature that can make someone attentive to the tiniest features of the environment. As I shuffle up the ridge of a 14er, I pause along the way for vibrant succulents, the illusive pika, or the marbled neons of boulders. Perhaps, as a writer, I am always paying attention to the tiniest details so that I can eventually describe them. But I would have no words for these things if I had not seen them.

I would not respect the environment as much as I do had I not been caught in some nasty, ground-shaking storms. I would not care about landscapes if I had not had some sort of formative experience within them, whether from self-epiphanies or connectedness with others. This may be a form of nostalgia, but it is not romanticism. Nature may terrify me: an avalanche could kill me along with a million other possibilities for injury and pain. I don’t need nature to necessarily be kind or safe to me for me to love it. But my formative experiences within it lead me to say: Amo: volo ut sis. I love you; I want you to keep going.

There is a similar Latin phrase: solvitur ambulando or “It is solved by walking.” It has a tongue-in-cheek origin: while debating the idea of motion, Diogenes stood up and walked across the room. Voila: “it is solved by walking.” The phrase has been expanded to larger idea of the benefits of walking and thinking. A common Victorian “walk in the garden” was the scene of dramatic discovering, fascinating conversations, and conflict resolution. “Walk it off,” we tell people who are upset. “Go for a walk” or take a breather. We walking, get out, and discover something larger.

III.

“I am convinced that experience and emotion are what will save the environment,” I told a friend after defending my research on psychological perspectives and ecology. “Have fun. You could spend years trying to defend that idea,” she retorted. “Maybe, I will!” I responded back, a little defensive.

If the studies are to be believed, then our generation is situated on the tipping point of action. There is still hope and energy that can be expelled towards saving the outdoors spaces we live, play, and thrive in. But it might take a different angle or vantage point of connection to reach an apathetic society. It’s about using every tool (activism, trail clean ups, data and analysis) at our disposal, even poetry.

It’s about using every tool (activism, trail cleanups, data and analysis) at our disposal, even poetry.

Percy Shelly said, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.” We can take this, in a larger sense, to say that those who can tap into the emotions of people can help develop better politics. Those who have tapped in to what they love and the experiences within that can lead the way for others to have a felt connection to these diminishing spaces.

“Amo: Volo ut sis,” We dance, shout, sing, and feel as the sun shines vibrantly before us.

Photos by Gale Straub

Find Haley Littleton on Instagram and read more of her writing on her website.

I’m taking a small break from writing a legal brief for round 3 of our attempt to force our county to protect Western Toad per Washington’s Growth Management Act. I’ve done this so many times before in this and other issues that its now almost routine. Standard of review, statutory requirements, administrative rules, best available science, deficiencies in the county’s action . . . How I yearn to use words like “ostrich,” “insane, “we’re next!” But I don’t. I tell the story in dry legalese and scientific jargon. And when I’m in front of the Hearings Board I will search their faces for some sign, glimmer, spark suggesting that they recognize that there is a real world whose continued existence depends on that emotionless bleached language.